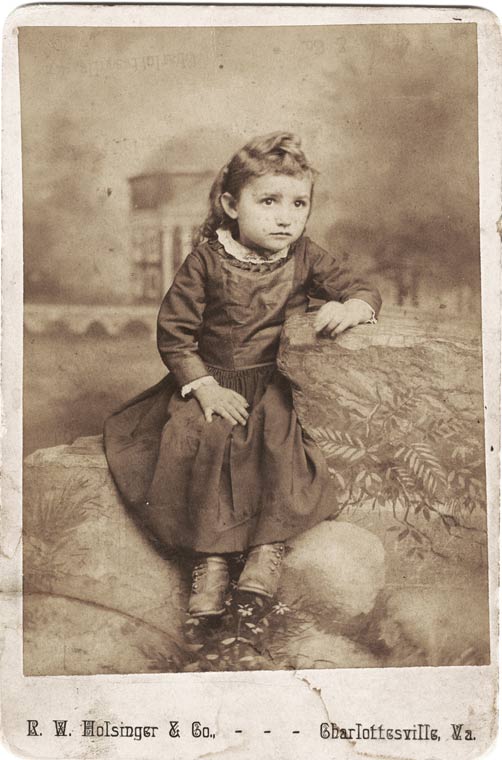

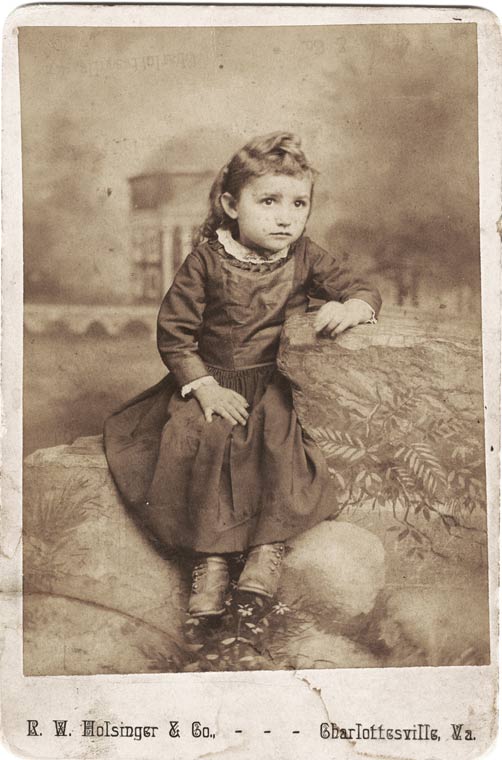

from the Baltimore-Pritchett collection, Mamie Starkes, c. 1892

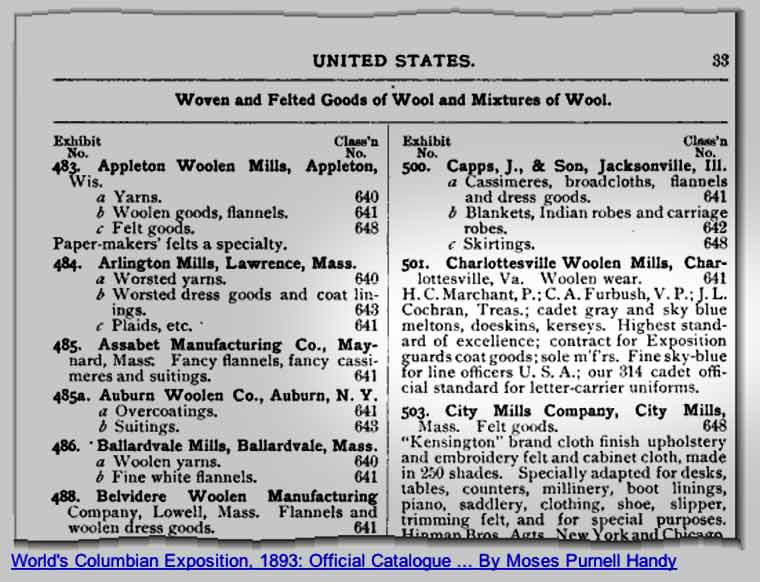

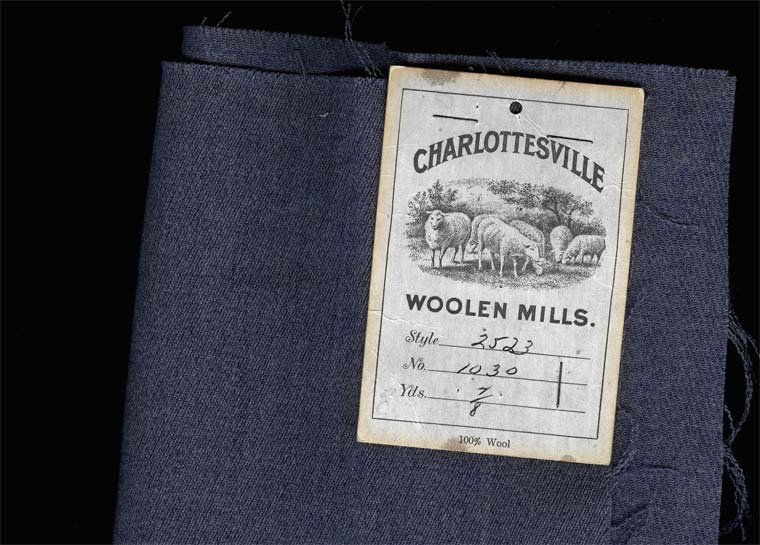

If Marchant believed that his major difficulties could be solved by a new infusion of capital, there were others equally sanguine who were willing to risk their money in the Factory. Marchant and his son, Henry, joined with John Wood, M. L. Anderson, T. J. Wertenbaker, and John C. Patterson to form the Charlottesville Manufacturing Company. Chartered as a joint-stock company by an act of the Virginia General Assembly passed on February 4, 1860, the new organization was authorized to acquire capital of not less than $12,000 nor more than $100,000 by selling stock at fifty dollars a share. The company received permission to own as much as 500 acres of land and "such personal property as they may deem necessary and proper for carrying on the manufacture of cotton, wool, flour, corn meal and tobacco,? the grinding of plaster? and the sawing of lumber. On March 20, books were opened in Charlottesville at the counting room of Patterson. Within a month the firm was organized with George Carr serving as president and John Marchant, who deeded his property to the company, acting as general agent. From Baltimore an experienced man was procured to supervise the manufacturing operations, Jones having disappeared from view during the preceding years. From the existing advertisements of the new concern it appears that the processing of wool into rolls for home weaving and the manufacture of cotton and wool into jeans and linseys had become the principal interest of the mill. Custom service was stressed and and the traditional barter type exchange of raw wool for finished cloth continued. Whatever the proportion of its income the mill secured from its subsidiary operations, the accent on a more specialized product typified a maturing textile firm. The mere formation of the company was in itself evidence of a spirit of confidence--a spirit which outlasted great misfortune to blossom forth after the war with renewed energy.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Baltimore, Poindexter History, Starkes