Sunday, April 12, 2009

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

171

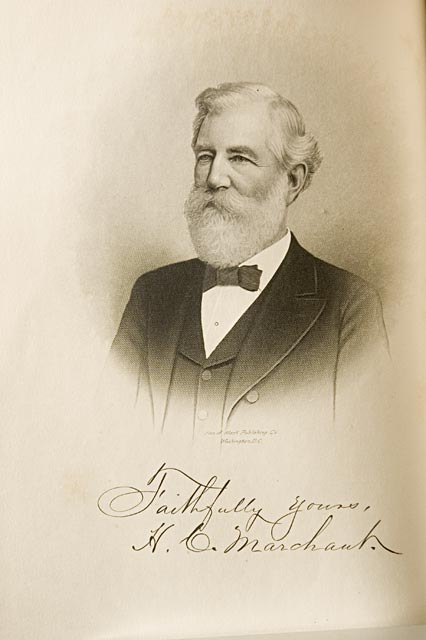

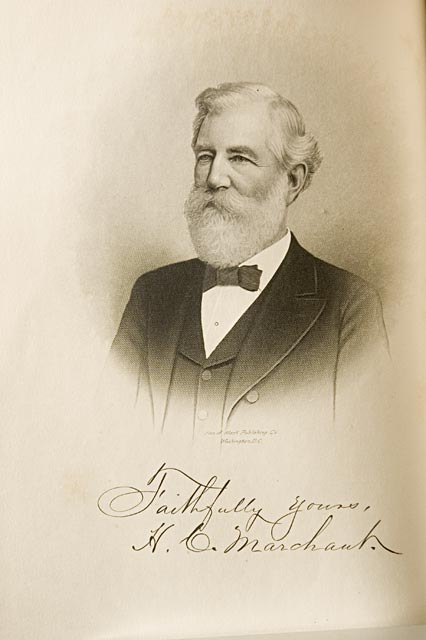

In an 1881 company report, Marchant made a telling statement regarding his attitude towards his workers?a statement that would set the tone for the mill village for decades to come:

"The property of a manufacturing company must ultimately rest on the efficiency and fidelity of its labor. It must be impaired by whatever impairs the comfort and morale of its operatives. It must be promoted by whatever promotes their self respect, elevates their character, and cultivates local attachments and the home feeling. Nor is it easy to estimate the pecuniary advantages of such a liberal policy as shall strengthen our hold on the entire body of employees, and more particularly on those whose value is apt to bring tempting offers from abroad."

Personal ethics formed the central core of Marchant's life and informed his company's policies as well. Prospective employees were assessed to ensure that they were "of good character." The people holding management positions had to exhibit exemplary character in addition to possessing the required strong work skills and leadership abilities. As a result, Woolen Mills employees developed a reputation in the greater Charlottesville community for responsibility and honesty, a fact that aided them when applying for credit from banks and store owners.

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant

Monday, December 29, 2008

blessing in disguise

Riverview Cemetery

The fire of 1882 was a blessing in disguise. It enabled the company to install new, efficient machinery and to expand its facilities. The fire also opened the door to new sources of capital, and the mill received its share of the Northern money which flowed into the New South after Reconstruction and the revival of prosperity. But it is only by coincidence that the date of this development fits into old conceptions about the origins of the New South.

The nature and causes of Southern industrial growth after the War of Secession have been matters of dispute among historians. The traditional view, fostered by such apostles of the New South as journalist Henry Grady, was popularized by Broadus Mitchell. According to Mr. Mitchell, Southern industry prior to 1880 was practically in the Middle Ages. In that year a sudden industrial revolution seized the South. Northern funds, combining with a burst of sectional interest, brought the region within a few decades to an industrial Renaissance. --Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History, Riverview Cemetery

Sunday, August 3, 2008

footnote

In order that "his high ideals, abounding faith, and honesty of purpose may live after him as an inspiration to future generations," Marchant's second wife, Fanny Bragg Marchant, bequeathed the bulk of his estate to the University of Virginia on her death in 1926. This gift provided for a loan fund for "deserving and needy students" and for two annual fellowships of $450 each to be given to students studying to be medical missionaries or preparing to enter the ministry. Bearing Marchant's name, these awards were fitting memorials to a man who contributed much to the "industrial, civic, educational and religious life" of Charlottesville. Will of Fanny Bragg Marchant in Comptroller's Office, University of Virginia.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

footnote

In order that "his high ideals, abounding faith, and honesty of purpose may live after him as an inspiration to future generations," Marchant's second wife, Fanny Bragg Marchant, bequeathed the bulk of his estate to the University of Virginia on her death in 1926. This gift provided for a loan fund for "deserving and needy students" and for two annual fellowships of $450 each to be given to students studying to be medical missionaries or preparing to enter the ministry. Bearing Marchant's name, these awards were fitting memorials to a man who contributed much to the "industrial, civic, educational and religious life" of Charlottesville. Will of Fanny Bragg Marchant in Comptroller's Office, University of Virginia.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Tuesday, December 4, 2007

survival

kitchen for "Piraeus" (the Marchant House)

The textile mills were caught in the process of filling autumn and winter orders. A large amount of short-term notes which had been received in payment for goods was defaulted. Mills became hard pressed for cash, many being forced to close down, others driven into bankruptcy. Following the immediate shock, stagnation gripped the industry and lasted until 1880.

How, one may ask, did the embattled Charlottesville mill succeed so well while powerful textile interests like the Sprague mills in New England with assets of $20,000,000 fell victim to the panic? First, it should noted that the lack of a preferred stock issue precluded a constant drain on resources. Common stock dividends could be and often were withheld. Furthermore, its wool purchases were much smaller than those of large mills and frequently were obtained from local farmers at prices which probably fluctuated less radically than the world market. In addition, the panic and depression of the 1870's caused a shift in demand to the coarser, cheaper goods made by the Charlottesville Woolen Mills during that era. Other factors could be mentioned--for example, the lower costs of labor in the South--but one especially deserves notice. That was the intense sense of sectional pride with which local inhabitants regarded the Mill. --Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Sunday, November 18, 2007

entail great suffering upon our help

As early as 1850 mill management had tried to provide decent housing for its employees. By 1880 it rented out three houses and seven tenement dwellings. Henry Marchant lived in one of the houses, and plant manager John Tyler and his family occupied another. Fifty-five out of 60 workers lived in the remainder.--Andy Myers

Marchant echoed the sentiments of Randolph and detailed the problems recently faced. He recalled a break in the dam race in January, 1873, which halted operations for a month when spring orders were being filled. At the same time "considerable loss" resulted when a sudden drop in wool prices caught the mill with a large stock of raw materials. Then, just as these setbacks were being overcome, the panic of 1873 threatened to sweep all gains away. That year proved to be "the most unprofitable that the woolen manufacturing interest of' the country has had to do battle with." As Northern mills closed right and left, the board of directors seriously debated a suspension of operations. Many factors played a part in their decision to maintain production, according to Marchant:

To shut down our gates would result in serious injury to machinery from rust and other causes; entail great suffering upon our help, and probably necessitate their seeking employment elsewhere, scatter the trade secured after years of toil, and injure our credit beyond hope of recovery. Yet to run when individuals and corporations controlling millions were stopping, seemed almost out of the question. With an indebtedness of $30,000 maturing at an early date, nothing seemed left us but to make the effort, by selling for close profits, and realize, as far as possible, from capital then invested in wool and woolens. This decided on, our prices were reduced to so near an approximate to cost as would ensure sale to a good class of trade, and every exertion [was] made to effect this object at the earliest possible moment.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History, railroad

Sunday, November 11, 2007

day of rest

An interesting question arises. Why was Marchant not president of the company from the beginning? The main reason apparently was that he did not own controlling interest in the company. As in the case of his father previously, the price he paid for additional capital was loss of personal control. By prearrangement, the new company had bought out Marchant for $30,500 and assumed the debt owed to Furbush and Gage. Marchant reserved the right to buy 280 shares at par, but whether he did so is unclear. Apparently, the Flannagan interests at first united to secure control, but by 1875 B. C. Flannagan had sold his stock and left Charlottesville. It is not clear why Randolph became president in 1873, unless it was to give standing to the company. Meanwhile, Marchant?s excellent work as superintendent attracted great praise, and his own financial connections grew. That he secured ascendency in 1875 and retained it until his death was more a measure of his ability than of his financial power, for he never owned a controlling block of stock.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History, Union Chapel

Friday, November 9, 2007

Marchant shouldered the burden

Meanwhile as superintendent, Marchant had acted as the real helmsman, plotting a careful course through the troubled waters of panic and depression. Having impressed his associates with his abilities in both the administrative and manufacturing phases of the business, Marchant was thereupon elected president as well as superintendent.

While economy in salary outlay was a factor in giving virtually complete direction of the operations to Marchant, more important were his competence, his energetic and forceful personality, and his ambition to make the mill a success. The move proved a wise one. As much as one man could, Marchant shouldered the burden of the factory for thirty-five years, and its ultimate success was in large measure his personal accomplishment. --Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Monday, November 5, 2007

locally owned

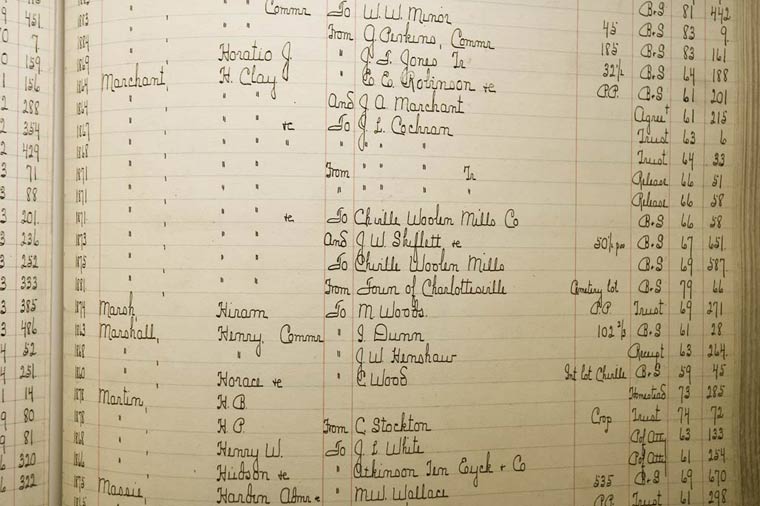

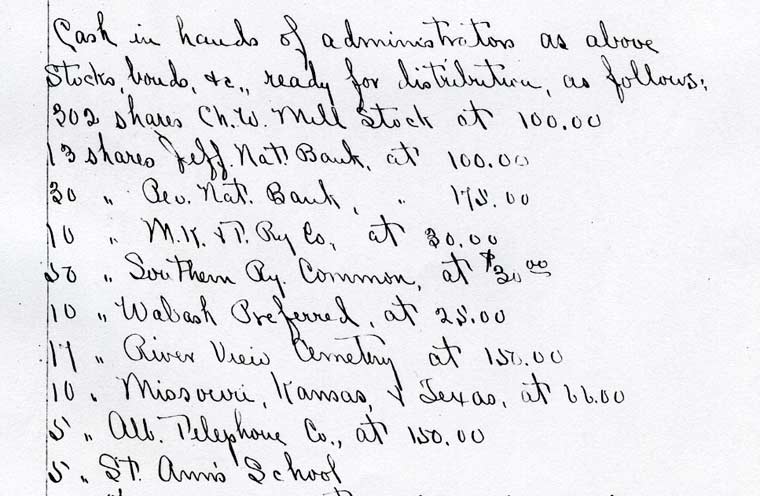

Unlike his father, Marchant never owned a majority interest in the Woolen Mill. At the time of his death HCM held 302 shares of Woolen Mills stock.-Albemarle County FB13 Page 448

What Northern capital seeped into the company prior to 1882 came mainly in the form of credit rather than the sale of stock. Thereby the mill deviated somewhat from the pattern followed by many industries in the New South, especially by cotton textile mills. The general method was to finance purchases of machinery from the North by selling the manufacturer stock in Southern enterprises.

Under the charter, capitalization was limited to a minimum of $50,000 and a maximum of $200,000, to be raised through the sale of stock at fifty dollars a share. Operations were placed under an eleven-man directory, selected annually by the stockholders and functioning through officers selected from and by the board. Five directors constituted a quorum. --Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

Marchant's vision

By his own dogged determination Henry Clay Marchant had chiseled a niche in Charlottesville for a new wool manufacture. Oriented primarily toward a local market, it produced the type of cloth in which Northern competition was least severe. But Marchant's vision was broader; an expanding market and a larger plant were the goals of the young, dynamic Marchant. Once again he approached Charlottesville friends for help. This time he presented an impressive accomplishment, demonstrating not only the feasibility of a woolen mill but his own financial acumen as well. And this time he met with a ready response. The result was a new company organized under the charter of December, 1868.

The granting of this charter inaugurated a new era. The woolen mill, finally freed from the limitations imposed by the resources of a single owner, was rapidly molded into the corporation which exists to this day.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

a mass of flames

photo from the Emory collection

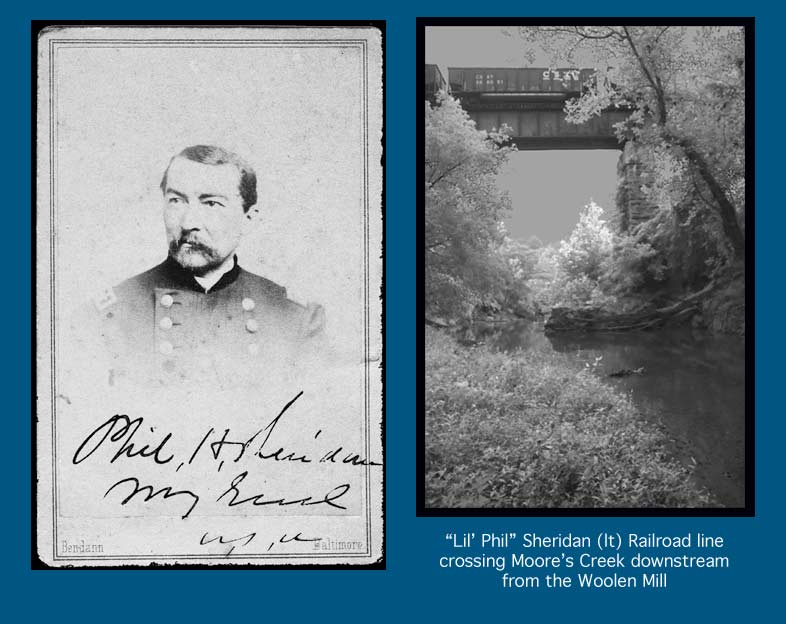

Practically over the roof of the factory extended an iron bridge on the Virginia Central line to Richmond. In order to warp the rails and burn the ties, coals still red-hot from recent use were carried by the soldiers from the mill furnace to the bridge. When a few pieces fell upon a greasy floor the factory quickly became a mass of flames. In this undramatic and unintentional fashion the mill became a casualty of the war. Henry Marchant did not witness the disaster. As the Union force entered Charlottesville, he had hobbled off to the hills on the southeast, driving his livestock ahead to save them from hungry enemy soldiers. From Carter's Mountain he watched smoke rising above the town and in the vicinity of "Pireus" without knowing what was burning. Not until after Sheridan continued south on March 6 did Marchant return home to discover the grave financial and sentimental loss he had suffered. His family and home were untouched, but his chief means of livelihood was gone.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Civil War, Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Friday, October 12, 2007

"strive to excel"--HCM

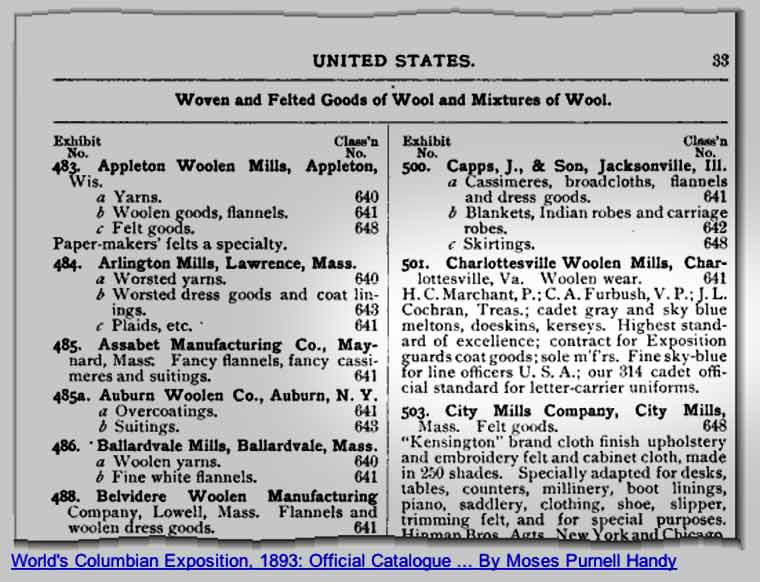

Charlottesville Woolen Mills manufactured cloth for the 1893 "worlds fair" guards' jackets. Digitized by Google

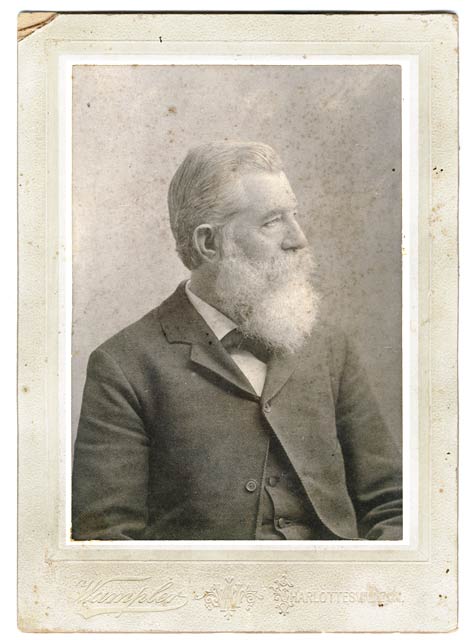

Henry Marchant was a representative of the curious union of business and religion which sees God's hand in every commercial success or failure. "He conscientiously believes," wrote a contemporary in 1906, "that whatever success he has achieved is due to the guidance of an overruling Providence, and that it is his solemn duty to point others to the divine Pilot." Recommending the Bible to "all who wish to find the true way and the true life," Marchant offered special advice to young men: "Work, work, strive to excel. If an employe [sic], strive to faithfully and conscientiously discharge whatever duties you undertake, and make your services indispensable to your employer; and, above all, ask God's guidance and help, that you may live a sober, unselfish, righteous, and useful life." Marchant paid more than lip-service to his religious beliefs. He became an active Episcopal layman, and toward his own employees he maintained a spirit of benevolent paternalism and genuine interest in their physical and moral well-being.

--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

his left leg was shattered

Riverview Cemetery, H.C. Marchant purchased this family plot in December, 1894

It will be recalled that Henry Clay Marchant was among the original investors who formed the short-lived Charlottesville Manufacturing Company. Born on April 1, 1838, in Charlottesville where he grew up, he had been educated in local private schools. Marchant at seventeen left his father's factory and dry goods store, moved to Petersburg, and became clerk for a grocer. He remained there in the mercantile business until the outbreak of the war. In April, 1861, he enlisted in Company A, 12th Regiment, Virginia Volunteer Infantry, serving until June 25, 1862, when on the first day of the Seven Days Battle near Richmond his left leg was shattered by a minie ball. Disabled, Marchant used crutches for over a year after Appomattox. In 1863, he married Elizabeth R. Whitehead of Petersburg and began searching for a business opportunity. It was at that point that he purchased the enterprise with the destiny of which his own for half a century would be intimately intertwined.--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Civil War, Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History, Riverview Cemetery

Monday, October 8, 2007

exigencies of war

Marchant family home, known as "Piraeus." Photo taken circa 1908, courtesy of the Marchant Family collection.

The house was built around 1840 and remains remarkably unchanged to this day. For many years, this was the largest house in Charlottesville.

In the photo, one can see the pair of lovely brick gutters that come from the house and traverse nearly the entire length of the front yard.

There is strong evidence that a tunnel runs under the gravel path shown between the gutters. The tunnel begins in the basement, under the front steps, and exits somewhere on the other side of the railroad tracks.

Inexplicably, in 1980, Albemarle County zoned this, and the other historic homes on the hilltop, Light Industrial. Since then, these properties have been under threat of demolition to make way for industrial development.

We'd welcome hearing from anyone interested in Piraeus, or who would like to join us in saving it from demolition. Victoria Dunham - Woolen Mills Road

Meanwhile, in the decade of the fifties, as Marchant strived to bolster the financial condition of the company, the nation had moved steadily to the brink of war, When the blow fell in 1861, the small corporation was swept along by the exigencies of the conflict. The Confederate government hastily commandeered or seized control over the multitude of small textile factories throughout the South and put them to work producing military cloths. The Charlottesville Manufacturing Company played its part in this phase of the Confederate war effort. By 1862, fifteen persons labored at spinning and weaving cotton and wool fibers into goods for soldiers' and laborers' wear. If an adequate wool supply had been available the mill might have experienced a boom similar to that in the northern wool factories. At least one other small wool factory sprang up nearby to meet the war-induced demand for cloth, making three such mills within a radius of some thirty miles. The Marchant factory alone had orders enough to give work to three times the number of people actually employed, but difficulties in transporting cotton and wool from the abundant supplies in Texas and the Lower South precluded undue expansion of the enterprise. The shortage of wool grew especially serious as the war progressed, and throughout the South private homes were frequently stripped of all available fabrics to meet the needs of the army. --Harry Poindexter

Labels: architecture, Civil War, Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Saturday, September 22, 2007

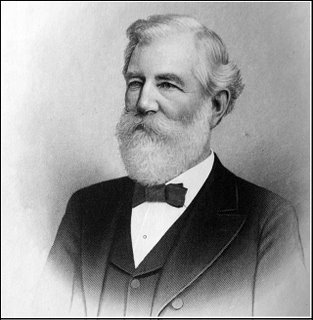

Henry Clay Marchant

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant, Poindexter History

Monday, June 18, 2007

Eppie Lou Fariss Marchant

Eppie Lou Fariss Marchant was the wife of Hampton Sidney Marchant, son of Henry Clay Marchant who owned the Charlottesville Woolen Mills from 1864-1910. "Eppie Lou" was born on June 22, 1880, in Alabama, and died on Sept. 19, 1918, in Charlottesville, Virginia during the flu epidemic. She is buried in the family plot at Riverview Cemetery.

Eppie (nee Eppe) Lou was the daughter of F. Ariadne Edwards and Lafayette Fariss of Sylacauga (Talladega County), Alabama. She married Hampton Sidney Marchant of Charlottesville, Virginia, at high noon on June 10, 1903. Why Hampton was so far from home over a hundred years ago -- and how he met his wife-to-be -- is a mystery to his descendents. Family lore, however, records that Lafayette Fariss was apparently very fond of Hampton, but he did not want to see his daughter move "north." Not so much that it was "the North", but that it was so far away. He was going to miss her.

Hampton and Eppie Lou had three children:

Mildred Elizabeth Marchant (1/18/1907 - 3/3/1907)

Henry Fariss Marchant (3/26/1908 - 10/12/1981)

Joseph Churchill Marchant (9/3/1911 - 2/--/1981)

Our father was Henry Fariss Marchant, who was 10 years old when his mother died. His recollections were few, but those he had were vivid. He recalled his mother as high spirited in temperament but frail in overall health. She had a low resistance to infections and viruses, which, no doubt, contributed to her passing at the age of 38. She was very involved in the church, and often took food to millworkers when they or their families were sick.

Daddy's favorite story about his mother: Eppie went into town once a week. She drove the buggy herself and often took her son Henry with her. The horse they owned was very spirited -- like Eppie Lou -- and loved to run. They would hook him up; get in; and take off. According to Daddy, they would fly down the hill, which is now Marchant Street, at top speed and run at full gallop all the way into town. Daddy would literally be hanging off the back of the buggy -- holding on for dear life! At the edge of town, Eppie Lou would stop...straighten her clothes, her hair, and her hat, and slowly and gracefully enter town.

So ends the story in the memory of a youngster.

P.S. Hampton Sidney Marchant lived until 1958 (outliving Eppie Lou by 40 years and never remarrying) and confirmed the part of the story about the spirited horse and stopping at the edge of town. Holding on for dear life was never confirmed, only experienced by a young boy named Henry.

Submitted by Henry Marchant's girls on June 8, 2007:

Carolyn Marchant Walker, Locust Grove, Virginia

Bobbie Marchant Anker, Charlottesville, Virginia

Kathy Marchant Hedick, Tallahassee, Florida

Labels: Henry Clay Marchant