rare executive ability

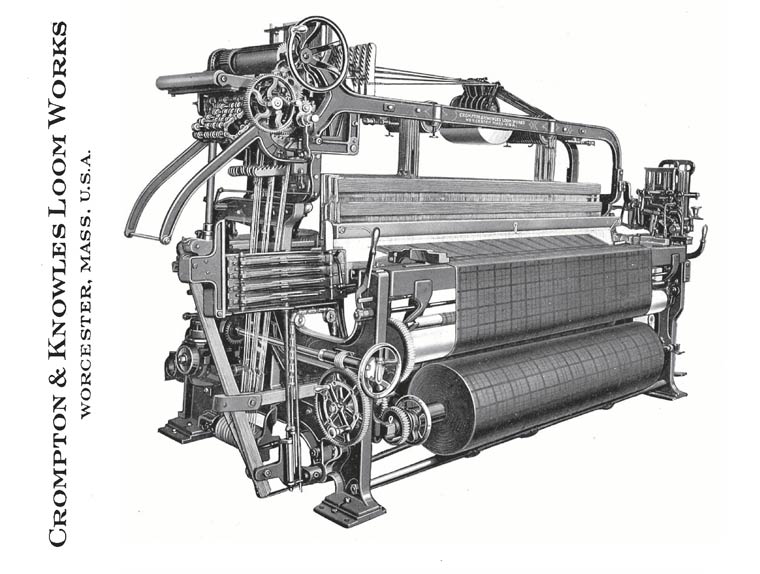

The board went, in fact, as far as New York City and hired Duryea Van Wagenen. Van Wagenen had been recommended to the board by mill owners at Danville, Virginia, despite the fact that he had had no experience with woolen mills. His chief qualifications were his "rare executive ability" and a reputation for "handling big affairs." Van Wagenen, it appears, had been connected with the National City Bank of New York. He also seems to have held an administrative post in at least one Southern textile mill. But these facts are not clear.

--Harry Poindexter

Labels: Poindexter History